Introduction to Marshallese Culture

by

Tony Alik, James Boaz, Christine Domnick, Ransen Hansen, Jr., Obet Kilon,

Benson Langidrik,Decency Langidrik,

Misako Lorennij, Ayson Maddison, Jefferson Paulis, Isabela Silk

Part I: The Origin of the Marshall Islands

According to legend, the Marshallese ancestors migrated into the islands from Southeast Asia some two thousand years ago. Linguistic and archaeological evidence would seem to support the theory that the first migrants arrived in the northern part of the island group and gradually settled throughout the two chains of islands, the Ralik and Ratak (Asian 2). Their migration to the islands was inspired by a number of reasons: warfare, over-crowdedness, and sense of adventure may have played a role in these movements. According to oral traditions, the settlers named their far-flung domain, Lollelaplap, which means "large expanse of ocean." Lollelaplap basically encompassed the 29 atolls and 4 islands that make up the Republic today.

The atolls and islands were formed from volcanic eruptions hundreds of thousands of years ago that formed the parallel island chains called Ralik (Sunset) and Ratak (Sunrise). The islands had been truly well settled by the time outsiders touched on these shores. English captains John Marshall and Thomas Gilbert were but two of these visitors, albeit later ones. Their names are prominently intertwined with the history of these islands, and our Kiribati neighbors to the south because they had the audacity to name these islands after themselves.

The atolls and islands were formed from volcanic eruptions hundreds of thousands of years ago that formed the parallel island chains called Ralik (Sunset) and Ratak (Sunrise). The islands had been truly well settled by the time outsiders touched on these shores. English captains John Marshall and Thomas Gilbert were but two of these visitors, albeit later ones. Their names are prominently intertwined with the history of these islands, and our Kiribati neighbors to the south because they had the audacity to name these islands after themselves.

Marshallese society is matrilineal people and arranged by hierarchy. At he top of the social tier were the Irooj (Chiefs), with the Alap (Noblemen), and Dri-Jerbal (Laborer) occupying the second and third tiers respectively. All land belonged to the Bwij or clan. Rights to land were inherited through the mother. According to oral traditions, every person had a birthright of land through the bwij. However, it was not individual ownership of the land rights and the responsibilities of each person depended on the position of the individual within the bwij, and the position of their bwij within the social classes that developed.

The traditional classes in society were distinct chiefs and commoners. The irooj laplap were the ones with the most power. Then there were the irooj rik, the lesser chiefs, and finally the kajur, or commoner. The irooj laplap were considered almost sacred, godly. Others stooped over and approached on their knees to show respect, and always obeyed the orders of their high chief. The irooj laplap received the best food, had the right to the best land in the Island, and had as many wives as they wanted. In return for these privileges, they were responsible for leading the people in general community work as well as on sailing expeditions and in war. Their power was normally in one part or the whole of one atoll alone. If a particular high chief was successful in war he could conquer and control several atolls.

These low-lying islands hold a lot of remarkable treasures. Although now in decline, the native Marshallese was once able navigators, using the stars and stick and shell charts, and the waves. They are still experienced in canoe building and hold annual competitions involving the unique oceanic sailing canoe, the PROA.

Part II: Religion

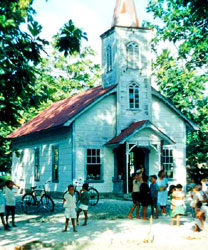

Today most Marshallese base their faith and identity in Christian belief. Christianity was introduced by the Protestant missionaries in 1857; however, before this, the Marshallese people had a religion of their own. Nowadays, Marshallese people know little of their old religion because the ancient faith and worship had fallen to decay long ago. It's hard now to gather up some fragmentary accounts of these important aspects of the native life. However, there are stories told by the elders that give us a little explanation of the old religion. Like all religions around the world, the old Marshallese religion had a set of beliefs that defined their religion: gods, spirits, death, afterlife, rituals, and magic.

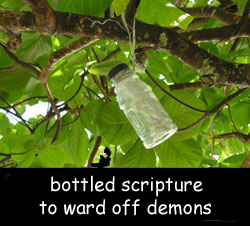

Instead of believing in one god, the Marshallese believed in many gods, but there was one God in particular that the people respected highly; a high God of all the other gods. According to James George Frazer, the Marshallese people respected this certain God, and offered him tributes: breadfruit, coconut, fish, etc. In their language, Iageach signifies "god." During war, or other important affair is to be an undertaken, solemn offerings were made, always in the open air (Frazier 81). Before a man would go out in search of food or fishing, he would have to offer something in his family's name to the gods. Other gods the people worshipped included spirits. Among these higher spirits are Wulleb, Lejman, Lajbuineamuen, Irojirilik, Lorok, Lewoj, and Lanej. It is believed that spirits like these would appear in dreams or sometimes they possessed a body of a human in order to be seen in the flesh. Some spirits were good and some were evil. The evil spirits were called Anjilik. These evil spirits were thought to cause sickness and sometimes possess the body of humans by stealing the souls out of their bodies. The people believed that when a person died, the soul may return and haunt the living. The deceased was enclosed in mats for burial, after which, a little canoe with a sail to it, and loaded with small pieces of other food, was taken to the seashore, or the leeward part of the island, and sent off, with a fair wind, to bear it far away from the island the spirit of the deceased; that if my not afterwards disturb the living.

Instead of believing in one god, the Marshallese believed in many gods, but there was one God in particular that the people respected highly; a high God of all the other gods. According to James George Frazer, the Marshallese people respected this certain God, and offered him tributes: breadfruit, coconut, fish, etc. In their language, Iageach signifies "god." During war, or other important affair is to be an undertaken, solemn offerings were made, always in the open air (Frazier 81). Before a man would go out in search of food or fishing, he would have to offer something in his family's name to the gods. Other gods the people worshipped included spirits. Among these higher spirits are Wulleb, Lejman, Lajbuineamuen, Irojirilik, Lorok, Lewoj, and Lanej. It is believed that spirits like these would appear in dreams or sometimes they possessed a body of a human in order to be seen in the flesh. Some spirits were good and some were evil. The evil spirits were called Anjilik. These evil spirits were thought to cause sickness and sometimes possess the body of humans by stealing the souls out of their bodies. The people believed that when a person died, the soul may return and haunt the living. The deceased was enclosed in mats for burial, after which, a little canoe with a sail to it, and loaded with small pieces of other food, was taken to the seashore, or the leeward part of the island, and sent off, with a fair wind, to bear it far away from the island the spirit of the deceased; that if my not afterwards disturb the living.

In the old religion, death was believed to be another passage to the island of the death, known as Eorerok and to another world with a different form of existence. People believed the deceased took along many of their personality characteristics with them after death. The dead continue to interact with the living, though their physical features change. They appear in other forms at times, with some appearing just the way they were when they had their last breath. It was believed that the dead like to stay nearby, often sanctioning those who misbehave. It was also believed that certain people are protected by the dead, probably close relatives, or the dead who favored an individual living person, but other ancestral spirits can frighten people. The most dangerous spirits were believed to come to an atoll from outside the Marshall Islands, often bringing misfortune, illness, or death.

Before the first missionaries stepped foot on these islands, the Marshallese believed in sacred rituals before going to war, burying of high chiefs or high Corps, before the marriage of male and female and before getting a tattoo. The village would give a feast for the warriors before they would be send to war, and the chiefs would say few words of advice and words of encouragement for the warriors. The people would prepare foods for the ritual. A special kind of lei called, Ulej in Kainemon, was prepared by the women for those going to war as a sign of peace and a safe return.

Rituals were also performed when a chief died. The people gathered for about seven to ten days with the chief's family. During this time, the people stayed with the family, preparing the body to be wrapped in traditional Marshallese mats before the body was laid to rest in the ground. This was also when the family chose an individual to be buried alive with the chief. The body was then carried on the ocean side to the burial side. It was believed that if the body were carried over lawns or near food gardens because everything would die or the trees would not bear fruits. After burial the people chose their new chief and welcomed him in celebration.

Sacred rituals were performed before a person would have a tattoo. A celebration was ordered by the chief for worship and to ask the god of tattoo if it was okay for the person to get a tattoo. Tattooing was prohibited when it rained by the chiefs, it was believed might bring bad luck, such as storms and misfortune. Prayer and offerings to gods was conducted to seek permission from the god to continue the tattooing process during the rain. Each tattoo was different for everybody. High ranking such as a chief had their own special tattooing design. As for the middle class, who are called Alap(s), also known as the landowners, and the lower class, which were called the Ri-Jerbal or the workers, also had their own tattoo designs. Women and men had separate designs.

Though Marshallese people are no longer using the old religion, there are some who still look to those ancient practices today, and some even continue to perform black magic, and taboos. Today, most Marshallese still respect their chiefs, but not as strongly as in the old days. The customs and manners of both the chief and the people have changed. Before, when a high chief died, the family chose a person who will be buried with the chief alive, but today, as people are Christians, it would be considered suicidal. Nowadays the Marshallese worships only one God.

Part III: Education

In the past, there was never a written language to record events. Any passed down skills, knowledge, and histories were done orally. Stories, chants, and songs were the most common methods used to educate anyone regarding the past, the people's history, and survival skills. One of the first things that people needed to do in order to survive was learn how to reap a living from the sea and land. Harvesting was one of the most important skills that ensured survival of each person. Since there weren't any imported foods; people had to rely on natural resources. Such foods that people had to rely on included breadfruit, papaya, pandanus, banana, coconut, taro, arrowroot, and many more.

There is a Marshallese saying that goes, Unare Peim loosely translated "heap the labors of your hands." An important labor was fishing. All men were required to learn how to fish. Since it was not a woman's job, they did not need to learn how to fish. Instead of using modern fishing lines, fishermen had to make their own from coconut husk (Bweo) by weaving the strands together to make the line called Ekkwal. For the hook, they had to use sharpened seashells from the Kaboor or giant clam, since there was nothing else more compatible to use for fishing. For most of the fishing methods, a certain kind of bait was used for fishing, called Karruk, a small land crab and Om, the hermit crab. These two things are certain kinds of crabs that are used for bait. Line fishing during the moonlit nights is called Totto, while the name for line fishing on moonless nights is called Junbon.

Other than using fishing lines and seashells, there have been 25 fishing methods identified, which means there is more to traditional fishing methods than we will ever know. Out of the 25 identified methods, we can describe five that were commonly used. One of these methods is called Alele, a technique often performed with large group of men. They weave coconut palm fronds together into a long net called mwieo. They force the fish to gather until the tide goes out and the fish can be easily speared. This method is often performed on Jaluit and other outer islands. Another method is called Kabwil, a technique often used at night. Fishermen weave a torch from old coconut palm fronds to attract fish at shallow areas. Once they are close enough, the fishermen spear the fish. This fishing method is also used a lot at outer islands. Still another method being used at night is called Bobo. The use of fire (now flashlights) is also included, but instead of using spears, fishermen use nets that are wovenfrom coconut stinnets (tree fibers). Once the torch is lit, a large number of flying-fish start flying out of the water, and the only thing the fishermen has to do is to catch them with the nets. Two similar fishing methods that are still being performed today are called Urok and Ilarak. Urok is a term that describes when fishermen are fishing within the lagoon. Ilarak is a term when fishermen are fishing on the oceanside. For both fishing methods, the use of Eo Jolok was mostly useful for fishing.

Other than using fishing lines and seashells, there have been 25 fishing methods identified, which means there is more to traditional fishing methods than we will ever know. Out of the 25 identified methods, we can describe five that were commonly used. One of these methods is called Alele, a technique often performed with large group of men. They weave coconut palm fronds together into a long net called mwieo. They force the fish to gather until the tide goes out and the fish can be easily speared. This method is often performed on Jaluit and other outer islands. Another method is called Kabwil, a technique often used at night. Fishermen weave a torch from old coconut palm fronds to attract fish at shallow areas. Once they are close enough, the fishermen spear the fish. This fishing method is also used a lot at outer islands. Still another method being used at night is called Bobo. The use of fire (now flashlights) is also included, but instead of using spears, fishermen use nets that are wovenfrom coconut stinnets (tree fibers). Once the torch is lit, a large number of flying-fish start flying out of the water, and the only thing the fishermen has to do is to catch them with the nets. Two similar fishing methods that are still being performed today are called Urok and Ilarak. Urok is a term that describes when fishermen are fishing within the lagoon. Ilarak is a term when fishermen are fishing on the oceanside. For both fishing methods, the use of Eo Jolok was mostly useful for fishing.

One of the most important lessons taught to men was navigation. Navigation was certainly the most difficult skill to learn since there was never any compass to help navigate from one island to another. Instead, they had to spend years memorizing hundreds of stars courses between the atolls and sea-ways, marks, cloud shapes, winds, and the flight of birds. The use of stick charts was also essential to understand as it showed sea-ways, marks, and islands. Only few men were able to master the navigational skills. Any man who mastered navigation skills was awarded a high title, or rank by an Iroij. This title is called Kajur or Kaben. A land parcel was also awarded to the Kajur or Kaben for his high achievements. Navigation was essential to help fishermen and people migrating from one place to another within the "Ralik" and "Ratak" chains.

One of the most important lessons taught to men was navigation. Navigation was certainly the most difficult skill to learn since there was never any compass to help navigate from one island to another. Instead, they had to spend years memorizing hundreds of stars courses between the atolls and sea-ways, marks, cloud shapes, winds, and the flight of birds. The use of stick charts was also essential to understand as it showed sea-ways, marks, and islands. Only few men were able to master the navigational skills. Any man who mastered navigation skills was awarded a high title, or rank by an Iroij. This title is called Kajur or Kaben. A land parcel was also awarded to the Kajur or Kaben for his high achievements. Navigation was essential to help fishermen and people migrating from one place to another within the "Ralik" and "Ratak" chains.

In the past, an art form of fighting -- called Maan Pa -- was taught to a few chosen men. This kind of fighting was taught secretly to few men who displayed good behavior and were mellow in heart. It was essential to learn how to fight in order to protect others from invading clans. If necessary, a clan might also invade other clans. So it was always good to be prepared. This art form is still being taught even to this very day, but only in few numbers as there are only a few who remember the art.

Before entering a battle, a chant would be sung by a woman to bring good luck to the men or to curse the opposing clans. Weapons used in battle included spears, clubs embedded with shark teeth, sling-shots, rocks, sharpened shells, and fire.

The last educational and survival method that was taught is weaving. Weaving was a common job among women, though men needed to learn how to weave in order to make their sails and nets. Since there wasn't any imported clothing or building materials in the past, people had to make their own. Clothing and mats were usually made by weaving together pandanus and hibiscus leaves. Women also learned to make handicrafts and tools to use for everyday use. Weaving required a lot of work and concentration.

Resources Consulted

Aea, Hezekiah. History in Ebon Atoll. Honolulou: February 7, 1863.

Frazier, James. Belief in Immortality and the Worship of the Dead. Vol III. The Belief Among The Micronesians. London: Macmillan and Co., 1924.

Juumemmej: Republic of the Marshall Islands Social and Economic Report, 2005. Asian Development Bank, 2006.Jumon, Honseki 2008 Interview

Komen, Juramen 2008 Interview

Lajuan, Newton 2008 InterviewNavigation & Stick Charts: www.rmiembassyus.org/Culture.htm

Marshallese Traditionalist Fishing Methods. RMI History Preservation Office Project.